|

The Final Battle Between Oates and Chamberlain

Late 1904 and early 1905

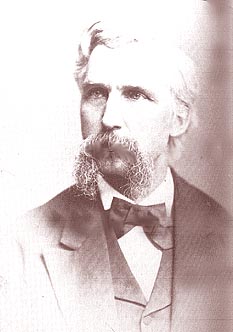

William

Oates fought one last battle with Joshua Chamberlain. Oates had been contemplating the placing of a monument to the

15th Alabama at Gettysburg, at exactly the spot where he believed his regiment had stood-on the far right of the rebel line

and within twenty yards of the federal line. Oates traveled to Gettysburg in the summer of 1904 to inspect Little Round

Top and to point out to park commissioners the line his regiment took on the afternoon of July 2, 1863. Oates walked

up Little Round Top to the exact spot where, he said, his regiment held its most foreward position. But the commissioners

who accompanied him said they had evidence that his regiment did not, in fact, advance so far as he believed. In support

of their position, they produced a letter from Joshua Chamberlain that contradicted Oates's memory.

Oates did not believe

he would have any trouble gaining approval for his monument, but after the 1904 inspections, he knew he would have to argue

his point with his old antagonist. Chamberlain simply would not agree that the 15th Alabama had gotten anywhere near as close

to his own line as Oates believed-and he was adamant on the point. The issue was taken up with Colonel John Nicholson

of the War Department, who attempted to adjudicate the two claims. In fact, the difference in distances involved was

minor-about fifty to seventy-five yards. But that did not mean the issue was unimportant, for Chamberlain claimed

that the placement of a monument to the 15th Alabama where Oates wished it to be would have placed the rebel regiment inside

his lines and exaggerated the success of their attack.

Frustrated by his inability to convince the War Department to

approve the monument, Oates finally wrote Chamberlain directly. Oates attempted to be conciliatory, but it took his

every effort, and the words are strained and cold:

"Co. Nicholson has sent to me your letter to him of the 16th ...which

I have carefully perused, and take pleasure in writing directly to you on the points involved. General, neither

of us are as young as we were when we confronted each other on Little Round Top nearly 42 years ago. Now, in the natural

course the memory of neither of us is as good as then. You speak in that letter of having corresponded with me and that

you had received two letters from me. I will not dispute your word for you are an honorable gentleman, but I have no

recollection of ever writing a letter to you, except at the present moment, nor do I remember ever to have received one from

you. I have heard and read much about you-among other things, the very complimentary notice of your soldierly and gentlemenly

conduct at Lee's surrender, in (General John B.) Gordon's book of Remenicinces [sic], but never had the honor of meeting you

after the war."

Oates went on to review his claim that a monument of the 15th Alabama Regiment should be placed at

Gettysburg at a point of its farthest advance. Oates said that he did not want to quibble as to exactly where that point

might be: "If you, General, will write to the Commissioners, or to its chairman, and say that you have no objection to erecting

it there, I assure you that there will be no inscription upon the shaft derrogatory to your command and if mentioned it will

be complimentary, for well do I know that no regiment in the Union Army fought any better or more bravely than your regiment

at that spot."

Chamberlain, however, would not agree. He reviewed Oates's application for the placement of the

monument and found fault with Oates's memory-claiming that he had previously written Oates, and that he had no objection to

a monument to the 15th Alabama. Nevertheless, he said, he could not agree to the placing of a monument on ground designated

by Oates, since the 15th Alabama did not reach that close to the Union lines or, as Oates claimed, "doubled back" his left

so that it almost touched his right. The attack of the 15th Alabama, Chamberlain implied, was simply not that successful.

The letter was testy:

"In [your] letter I find your impressions place me at a disadvantage in your estimation on two

very different grounds; first, in that your former correspondence by way of letter made so little impression on you

that you are led to deny having such correspondence; and secondly that you ascribe to my influence with the Government authorities

their refusal to permit the erection of a monument to the 15th Alabama on the ground where they fought. These suggestions

compel me to look over my vouchers to see if I have possibly been mistaken on topics of much importance as to involve my honor."

These

were fighting words since, in that time especially , a man's

"word of honor" could not be questioned lightly. Chamberlain

then went on to protest that he had "no objection whatever to the erection of a monument by you on the ground attained by

the 15th Alabama or any portion of it, expressing only the wish that this ground be accurately asscertained." Chamberlain

argued that Oates was simply wrong in his assumption about how close his regiment had come to the 20th Maine, or at what point

it had penetrated his lines, if it did at all-and therefore Chamberlain simply could not agree to the placing of the monument

on the ground that Oates designated.

There is where the issue ended, with no more correspondence between the two.

There was much more to the controversy, however, than Oates could have known. It now seems unlikely, in light of the

historical evidence, that the Gettysburg Park Commission was inclined to place any monument honoring the 15th Alabama at Gettysburg,

even had Chamberlain agreed with Oates on the details of the battle. After Chamberlain wrote to Oates, he sent a copy

of his letter to John Nicholson of the War Department's Gettysburg National Park Commission. Nicholson wrote back: "

I wish to congratulate you upon the dignified, manly, soldierly and gentlemanly way in which you have replied to him,"

Nicholson wrote. "It is very clear that General Oates has not the slightest idea of admitting the views of any one in

the controversy except himself." Nicholson added that the monument debate was being turned over to the chairman of the

commission. Several months later, the commission turned down Oates's request for a monument to the 15th Alabama on Little

Round Top.

Oates was deeply disappointed. He wanted the regimental monument to serve as a memorial not only to

those who fought there, but to his brother and his close personal friends, and had spent hours designing the monument and

writing its inscription:

To the memory of Lt. John A. Oates

and his gallant Comrades who fell here

July 2nd,

1863. The 15th Ala. Regt.,

over 400 strong reached this spot, but

for lack of support had to retire.

Lt.

Col. Feagin lost a leg.

Capts. Brainard and Ellison,

Lts. Oates and Cody and

33 men were killed, 76 wounded

and

84 captured.

Erect 39th Anniversary of battle,

by Gen. Wm. C. Oates who was

Colonel of the Regiment.

The

Chamberlain-Oates controversy over the 15th Alabama monument not only shows how the war lived on long after its guns were

silenced, but exemplifies the very real wounds that remained between its antagonists. The generation that had fought

the war was dying, and yet they had not forgotten the past. Even forty-two years after the events, the battle was fresh

in the minds of Chamberlain and Oates, despite the care they took in complimenting each other on their successful careers.

"I should be glad to meet you again, after your honorable and conspicuous career of which the trials and test of Gettysburg

were so brilliant a part," Chamberlain told the former Alabama commander in his last letter.

Yet, despite this formal

cordiality, Chamberlain and Oates never gave any indication that they would have really liked to meet each other; they never

talked, never addressed the same crowd or served in the same legislature. The only time they faced each other

directly was at opposite sides of the most important conflict of their day. But despite this, their lives, careers,

families, experiences of war and peace, and successes and failures are remarkable similar. Both grew up in modest surroundings,

in rual communities, where education and God were ever-present realities. Both were self-made men who became amateur

soldiers. Both excelled in battle, both served as governors of their state, both yearned for a seat in the Senate-both

were denied. Had they met, they would have had much to talk about. A list of the topics on which they might

have found common ground would be lengthy and an almost perfect reflection of their society's most important principles: both

mistrusted big government, believed in an elected elite of "the best men," thought political stability the engine of economic

growth-and had large ideas about the course of the American Republic.

The above text was taken from, "Conceived

in Liberty - Joshua Chamberlain, William Oates,

And the American Civil War" by Mark Perry - Viking - Copyright 1997

Enter subhead content here

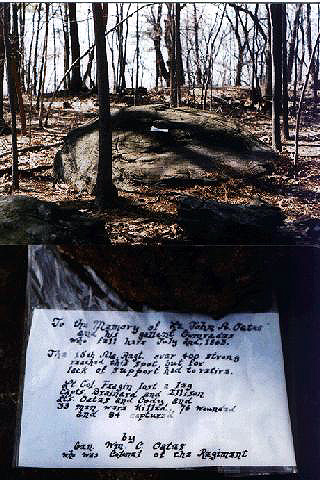

Message on the Rock

Col. William C. Oates identified the rock in the background

of the top picture as the one on which his brother, Lt. John A. Oates, was killed. He wished to erect a monument

on that site, but was denied permission to do so. The message on the rock-close up on the bottom picture-is the one

he wished to place on the monument, as written in the above writing about Oates, in the "The Final Battle between Oates and

Chamberlain.

|